Today is International Day of Persons with Disabilities, a globally recognised day dedicated to bringing people together who live with cerebral palsy, raising awareness and spreading education. We sat down with Kyle, a man who has Cerebral Palsy, to understand how being disabled affects his life, and affected him growing up.

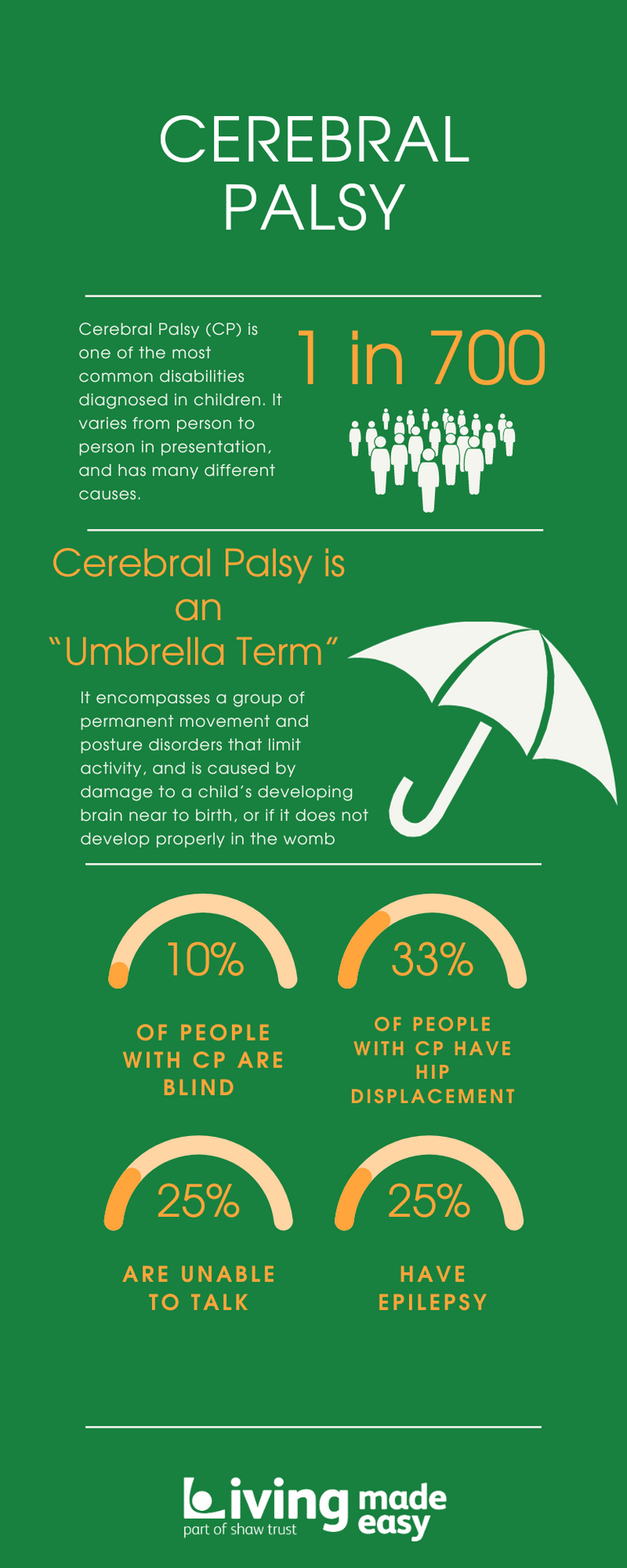

There are over 17 million people across the world living with Cerebral Palsy. It is a collection of lifelong conditions that primarily affect movement and coordination. It is usually caused by problems affecting the development of the baby’s brain whilst it is developing. There are many possible reasons for this, such as, but not exclusively: damage to the white matter of the brain, often because of reduced blood or oxygen: an infection caught by the mother during pregnancy: a stroke (bleeding in the baby’s brain): injury to an unborn baby’s head. It can also be caused by problems during, or shortly after birth. This can again be for several reasons, but most commonly it is because the brain temporarily does not get enough oxygen (asphyxiation) during a difficult birth, though it can be caused by other issues also.

The signs and symptoms of Cerebral Palsy appear during infancy, or during the pre-school years. It is most often diagnosed after the baby fails to reach certain milestones within the normal time range, such as learning to roll over, crawl, walk etc. Signs to look out for in your baby include the following: impaired movement associated with exaggerated reflexes, floppiness or spasticity of limbs and the torso: unusual posture, often because of poor muscle tone: involuntary muscle movements or spasms: unsteady walking. The most important thing to remember is that if you do notice any of these signs, talk to your GP. Many people with Cerebral Palsy also have difficulty swallowing, or an eye muscle imbalance and reduced range of motion. Treatment usually entails a combination of different therapies, such as physiotherapy, and occupational therapy. Having a child with CP doesn’t mean that they will have every symptom or complication possible. Every person with cerebral palsy is different and will experience it differently.

With that in mind, we believe that the best way to understand the condition and raise awareness is to listen to the real stories of people who have lived their lives with Cerebral Palsy and can give us a first-hand account of how it’s affected them.

We sat down with Egyptologist Kyle Jordan to talk about what it was like growing up with Cerebral Palsy. Kyle is a museum curator working in Oxford at both the Ashmolean and the Pitt Rivers museums. He has been curating collections of disability histories that exist within the museum collections. Disability histories and disabled experiences in history have started to gain traction in the academic world, but it has thus far always been kept on the periphery of the discussions.

“This is one of the first times in the UK where we have started to do it [tell disabled stories] with co-curation and co-production of disabled people.”

Kyle explained that in the development of these exhibitions they have specifically sought to work with disabled people to help them tell their stories.

As well as working as a curator, Kyle is working towards his PHD. He is exploring how we can begin to understand the experiences of disability in the past, through the evidence we have in the archaeological record.

“I am hoping to prove that human sensibilities towards bodily and mental differences have always fluctuated over time, and that not only have disabled people always been part of society, but valued members of it.”

I was given back, and they were given some information and told to go on their way.

Kyle and his family were not aware of his Cerebral Palsy until he was around two years old. His parents had a few initial concerns but pushed them aside and tried not to worry.

“When I still wasn’t walking by two years old the doctors did a bit more of a thorough examination, and I was diagnosed with CP.”

However, the diagnosis wasn’t the answer to everything that his parents had hoped it would be.

“I was given back, and they were given some information and told to go on their way.”

Kyle says his mum especially felt lost.

“She didn’t know where to start.”

True to his general attitude towards life however Kyle sees the silver lining. His diagnosis exposed his mum to this new world filled with doctors’ appointments, GP visits, physiotherapy, and other specialists. He says it is this that begun her on her journey to becoming first a paramedic, then a midwife.

When you get to adulthood, they sort of kick you out.

At the age of four or five Kyle’s life changed in a huge way. Whilst most children this age are running around and getting into all sorts of trouble, he couldn’t join in on this. Up until this point he had used a buggy pushed by his parents. Then, however he was fitted for his first wheelchair, which opened the world for him in a huge way and most importantly, enabled him to play with other children. The benefit of being in a wheelchair from so young was that the kids he was at pre-school with didn’t really treat him any differently from other children. When kids are younger, they tend to worry less about fitting in and ‘being cool’. They are more inclusive. Yes, they are curious and often ask questions that adults may be awkward about, but they are less inclined to be mean to impress others. Kyle said that he didn’t really feel any different from the kids that he was around.

Teenagers however and pre-teens can be a lot crueller. When Kyle moved from Yorkshire to Cornwall because of his dad’s work, he was greeted with less kindness and more bullying, as well as ostracization from the other children. This was coupled by a slowly increasing realisation of how limited his options were when compared to his peers. He couldn’t simply go out and play with the other kids on a whim. There are a lot more steps involved in everything that must be taken before even doing a simple task like going outside to play. And even then, you are at the whims of how accessible the world around you is.

“As I got older, I became more introverted because it felt like the easier thing to do.”

Growing up with someone who gets it.

Kyle’s older sister also has Cerebral Palsy. Although it does not tend to run in families, as it isn’t a genetic condition, Kyle and his sister share the diagnosis. This is extremely rare with one study stating that “the aggregation of children with CP in families is uncommon accounting for less than 2% of cases”. Kyle says that this came with both benefits and drawbacks, as do most things. They understood each other and what they were going through better than most, and they had each other for support. But it also created friction between them. Many disabled people experience what is known as ‘imposter syndrome’. Within the disability community this refers to the feeling of not being ‘disabled enough’, either by direct comparison to others, or in a wider sense. It often leads to people comparing their symptoms and difficulties to others as a benchmark of whether they feel they deserve help or sympathy etc. In Kyle and his sister’s case, this was the case. Kyle’s sister walks, albeit with an uneven gait due to both muscular problems and one leg being slightly shorter than the other. Kyle described the strain that was put on them, like many disabled siblings, because of a perceived inequality of attention given to the sibling with the more ‘severe’ symptoms. It puts a lot of pressure on family dynamics to navigate those difficult relations and feelings without much help from the outside world.

“When you’re disabled it is a huge part of who and what you are. It shapes your lived experience and how you experience the world around you. This can be a benefit, as it allows you to see the world differently and expose the cracks. But you are always so much more than just your disability.”